Classics? History? What's the Difference?

Many associate classics, or classical studies, as the study of ancient times. “Classical antiquity” is a term that is thrown around. But then, what about history? Are classicists historians as well? Where does archaeology fit into all of this? It’s confusing to someone who hasn’t studied these things, and so I thought I’d write up a little guide to help you out.

Classics

Classical studies, or just “classics” as they are called in so many (though growing fewer every year) school, is not defined broadly as the study of Ancient Greece and Rome, but rather as the study of Ancient Greek and Roman literature. It involves research on the written documents of those times. Classicists are, above all, linguists. They translate the works of poets, philosophers, politicians, historians, and others who lived in Ancient Greece and Rome, and try to put them into terms we can understand. They focus on writing, often without context of other aspects of history, though this has changed a lot in the last century. They tend to be interested in civilization: art, literature, and religion as it was written.

Traditionally, Latin and Ancient Greek were and still are the languages of classicists. But in more recent times, people realized they were missing parts of the picture, and now languages like Hebrew and Arabic, as well as other Mediterranean languages, might also be included in these studies.

Archaeology

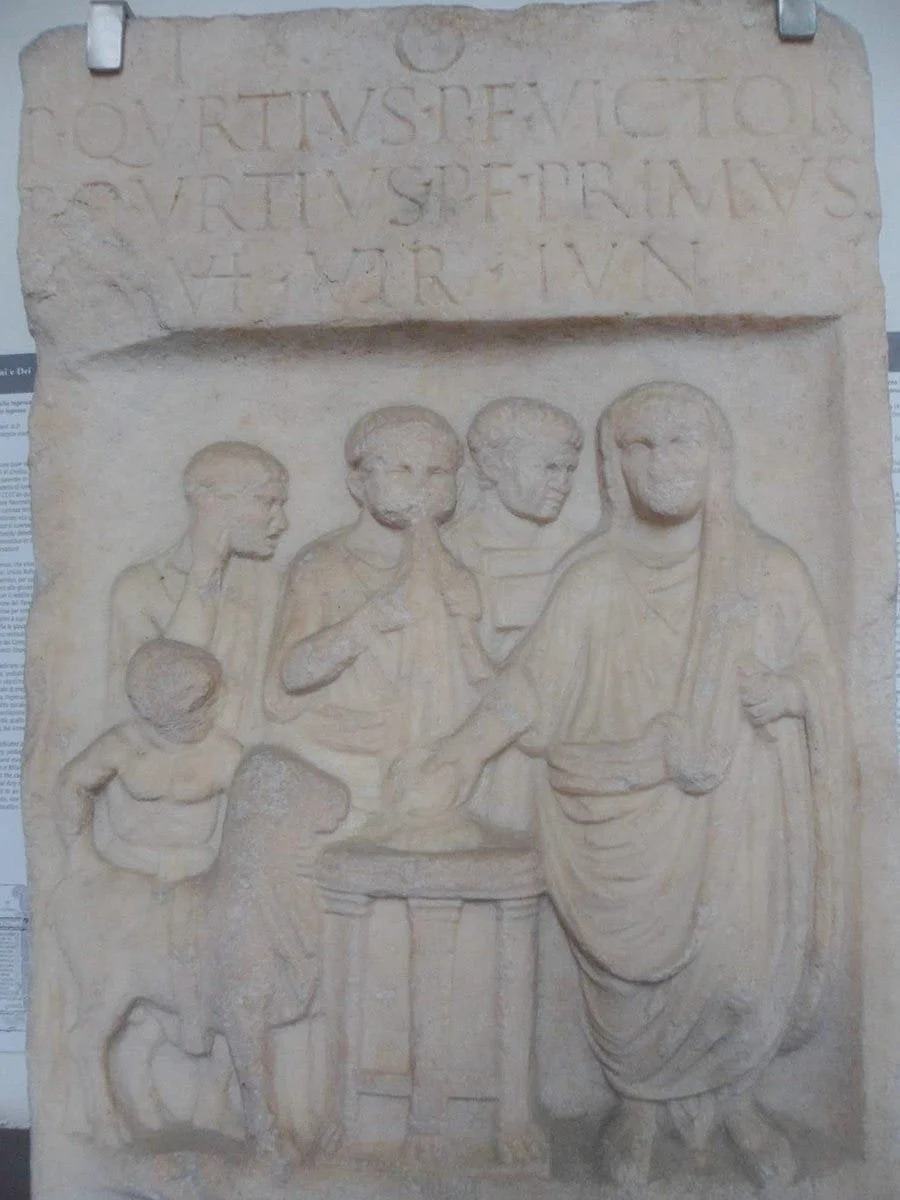

Archaeology is the study of material remains. Archaeologists work in the field, digging and excavating remains of ancient civilizations in order to learn more about the cultures and societies of their people. Classical archaeologists are those who specifically study the remains of Ancient Greece and Rome. Often, they are inspired by the research classicists have done, and incorporate classics into their work, but their work is not focused on the written word. Rather, they look at buildings, pottery, sarcophagi, temples, weapons, and other relics of material culture (the physical things a culture has left behind). Ruts in roads, bricks, and things that seem innocuous to the layperson’s eyes can be treasures to archaeologists. Even the ashes from ancient fires have stories to tell trained eyes. We tend to think of archaeologists in the field most often, excavating sites and digging with hammers, chisels, and brushes. But you are just as likely to find them in a laboratory doing chemical analyses or in a research library.

Ancient History

If classics is the study of the words of ancient peoples, and archaeology is the study of their relics, then history is taking those things and putting them into a larger context. It’s taking the words of the documents and reading between the lines to try to find the people behind them. It’s taking the ruts in the road and trying to figure out who made them and why. Who traveled those roads? Where were they going? Who walked and who rode? Who was carried and who were the carriers? Whose hands touched the pottery, and who ate the food that was prepared with it? Ancient historians study the society, culture, politics, military, and other aspects not just of the Greek and Roman people, but of those other cultures that mingled with them and helped shape them over time.

A Triumvirate of Studies?

All three of these subjects have their own nuances, and all of them overlap. There are sub-categories of each that look very much like one of the others, and sometimes there is disagreement about the definitions. In fact, people disagree on what exactly the realms of each are. What I have here is a very simplified explanation for the layperson to start to understand terminology of these branches of study. I myself have studied classics and ancient history, but very (very) little archaeology. I consider myself a historian, and that is what I have my graduate degree in. I do, however, look at the work of archaeologists to inform my historical study, and the work of classicists is very valuable as well. I would not be able to do good history without relying on the work from the other two fields. For instance, I can easily translate a text in Latin, but if I sent the text to a classicist, they could give me a more nuanced translation than I could do. They would be able to say that one writer used a term in a certain way, yet another used it in a subtly different way, and they would be able to look at it in a context to figure out what my text actually might have meant. If the text was written on parchment or on a stone monument, and archaeologist would be able to give me more context from where the stone came from, how old the parchment was, etc. Likewise, the other two fields benefit from history. It’s like a triumvirate (based on Latin for “three men”), but with fields of study rather than men. Though, hopefully, this triumvirate (triumerudiciate? Where is a classicist when I need them!) is far more effective and amiable than those of Ancient Rome!